Classification / Names

Common names from other countries

Main reference

Size / Weight / Age

Max length : 245 cm FL male/unsexed; (Ref. 5203); common length : 160 cm FL male/unsexed; (Ref. 9684); max. published weight: 260.0 kg (Ref. 5203); max. reported age: 20 years (Ref. 168)

Length at first maturity

Lm 119.0, range 120 - 130 cm

Environment

Marine; pelagic-oceanic; oceanodromous (Ref. 51243); depth range 50 - 2743 m (Ref. 57178)

Climate / Range

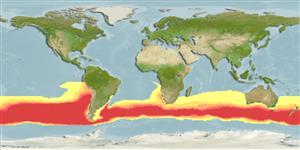

Temperate; 5°C - 20°C (Ref. 168), preferred 16°C (Ref. 107945); 8°S - 60°S, 180°W - 180°E (Ref. 54921)

Distribution

Atlantic, Indian and Pacific: temperate and cold seas, mainly between 30°S and 50°S, to nearly 60°S. During spawning, large fish migrate to tropical seas, off the west coast of Australia, up to 10°S. Highly migratory species, Annex I of the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (Ref. 26139). If the current exploitation continues, the population will be below 500 mature individuals in 100 years (Ref. 27905).

Countries | FAO areas | Ecosystems | Occurrences | Introductions

Short description

Vertebrae: 39. A very large species, deepest near the middle of the first dorsal fin base. Swim bladder present. Lower sides and belly silvery white with colorless transverse lines alternating with rows of colorless dots. The first dorsal fin is yellow or bluish; the anal fin and finlets are dusky yellow edged with black; the median caudal keel is yellow in adults.

IUCN Red List Status (Ref. 115185)

Threat to humans

Harmless

Human uses

Fisheries: commercial; aquaculture: commercial; gamefish: yes

Tools

Special reports

Download XML

Internet sources

Estimates of some properties based on models

Phylogenetic diversity index

PD50 = 0.5039 many relatives (e.g. carps) 0.5 - 2.0 few relatives (e.g. lungfishes)

Trophic Level

3.9 ±0.53 se; Based on food items.

Resilience

Low, minimum population doubling time 4.5 - 14 years (K=0.14-0.15; tm=8-9; tmax=20; Fec=14 million)

Vulnerability

High to very high vulnerability (67 of 100)

Price category